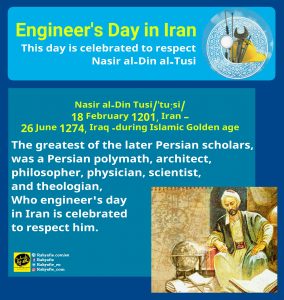

According to rahyafte (the missionaries and converts website):ost of countries all around the world have their own engineer day in diverse date according to a unique event or associated to a known engineer in one field.Specially in Iran week of 19 to 25 February – (24 February every year) is organized for engineer day. This day is celebrated to respect Khawaja Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Persian scholar.

Nasir al-Din Tusi/tu:si/)18 February 1201 in Tus of Khorasan, Iran – 26 June 1274 in Baghdad, Iraq during Islamic golden age ), was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. The Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) considered Tusi to be the greatest of the later Persian scholars.

Biography

Nasir al-Din Tusi was born in the city of Tus in medieval Khorasan (northeastern Iran) in the year 1201 and began his studies at an early age. In Hamadan and Tus he studied the Quran, hadith, Ja’fari jurisprudence, logic, philosophy, mathematics, medicine and astronomy.

He was apparently born into a Shī‘ah family and lost his father at a young age. Fulfilling the wish of his father, the young Muhammad took learning and scholarship very seriously and travelled far and wide to attend the lectures of renowned scholars and acquire the knowledge, an exercise highly encouraged in his Islamic faith. At a young age he moved to Nishapur to study philosophy under Farid al-Din Damad and mathematics under Muhammad Hasib. He met also Attar of Nishapur, the legendary Sufi master who was later killed by the Mongols, and he attended the lectures of Qutb al-Din al-Misri.

In Mosul he studied mathematics and astronomy with Kamal al-Din Yunus (d. AH 639 / AD 1242), a pupil of Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī. Later on, he corresponded with Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, the son-in-law of Ibn Arabi, and it seems that mysticism, as propagated by Sufi masters of his time, was not appealing to his mind and once the occasion was suitable, he composed his own manual of philosophical Sufism in the form of a small booklet entitled Awsaf al-Ashraf “The Attributes of the Illustrious”.

As the armies of Genghis Khan swept his homeland, he was employed by the Nizari Ismaili state and made his most important contributions in science during this time when he was moving from one stronghold to another. He was captured after the invasion of Alamut Castle by the Mongol forces.

Works

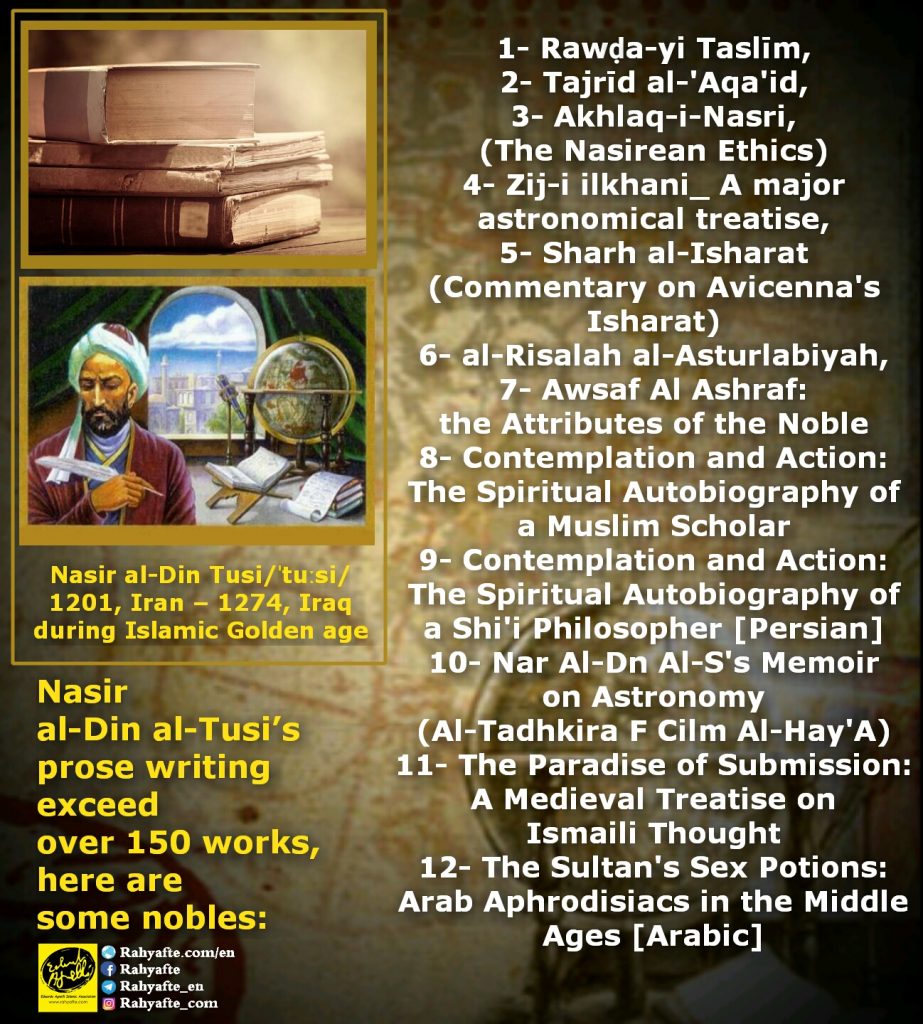

Tusi has about 150 works, of which 25 are in Persian and the remaining are in Arabic, and there is one treatise in Persian, Arabic and Turkish.

Here are some of his major works:

Achievement

During his stay in Nishapur, Tusi established a reputation as an exceptional scholar. “Tusi’s prose writing, which number over 150 works, represent one of the largest collections by a single Islamic author. Writing in both Arabic and Persian, Nasir al-Din Tusi dealt with both religious (“Islamic”) topics and non-religious or secular subjects (“the ancient sciences”). His works include the definitive Arabic versions of the works of Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Autolycus, and Theodosius of Bithynia.

Astronomy

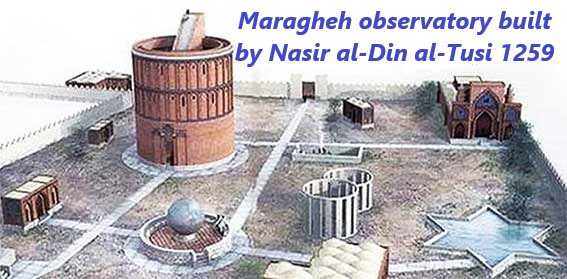

Tusi convinced Hulegu Khan to construct an observatory for establishing accurate astronomical tables for better astrological predictions. Beginning in 1259, the Rasad Khaneh observatory was constructed in Azarbaijan, south of the river Aras, and to the west of Maragheh, the capital of the Ilkhanate Empire

Based on the observations in this for the time being most advanced observatory, Tusi made very accurate tables of planetary movements as depicted in his book Zij-i ilkhani (Ilkhanic Tables). This book contains astronomical tables for calculating the positions of the planets and the names of the stars. His model for the planetary system is believed to be the most advanced of his time, and was used extensively until the development of the heliocentric model in the time of Nicolaus Copernicus. Between Ptolemy and Copernicus, he is considered by many to be one of the most eminent astronomers of his time. His famous student Shams ad-Din Al-Bukhari was the teacher of Byzantine scholar Gregory Chioniadis, who had in turn trained astronomer Manuel Bryennios about 1300 in Constantinople.

For his planetary models, he invented a geometrical technique called a Tusi-couple, which generates linear motion from the sum of two circular motions. He used this technique to replace Ptolemy’s problematic equant for many planets, but was unable to find a solution to Mercury, which was solved later by Ibn al-Shatir as well as Ali Qushji. The Tusi couple was later employed in Ibn al-Shatir’s geocentric model and Nicolaus Copernicus’ heliocentric Copernican model. He also calculated the value for the annual precession of the equinoxesand contributed to the construction and usage of some astronomical instruments including the astrolabe.

Ṭūsī criticized Ptolemy’s use of observational evidence to show that the Earth was at rest, noting that such proofs were not decisive. Although it doesn’t mean that he was a supporter of mobility of the earth, as he and his 16th-century commentator al-Bīrjandī, maintained that the earth’s immobility could be demonstrated, but only by physical principles found in natural philosophy. Tusi’s criticisms of Ptolemy were similar to the arguments later used by Copernicus in 1543 to defend the Earth’s rotation.

About the real essence of the Milky Way, Ṭūsī in his Tadhkira writes: “The Milky Way, i.e. the galaxy, is made up of a very large number of small, tightly-clustered stars, which, on account of their concentration and smallness, seem to be cloudy patches. because of this, it was likend to milk in color.” Three centuries later the proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when Galileo Galilei used a telescope to study the Milky Way and discovered that it is really composed of a huge number of faint stars.

Mathematics

Al-Tusi was the first to write a work on trigonometry independently of astronomy. Al-Tusi, in his Treatise on the Quadrilateral, gave an extensive exposition of spherical trigonometry, distinct from astronomy. It was in the works of Al-Tusi that trigonometry achieved the status of an independent branch of pure mathematics distinct from astronomy, to which it had been linked for so long. He was the first to list the six distinct cases of a right triangle in spherical trigonometry.

This followed earlier work by Greek mathematicians such as Menelaus of Alexandria, who wrote a book on spherical trigonometry called Sphaerica,and the earlier Muslim mathematicians Abū al-Wafā’ al-Būzjānī and Al-Jayyani.

In his On the Sector Figure, appears the famous law of sines for plane triangles. He also stated the law of sines for spherical triangles, discovered the law of tangents for spherical triangles, and provided proofs for these laws

Biology

In his Akhlaq-i Nasiri, Tusi wrote about several biological topics. He defended a version of Aristotle’s scala naturae, in which he placed man above animals, plants, minerals, and the elements. He described “grasses which grow without sowing or cultivation, by the mere mingling of elements,”as closest to minerals. Among plants, he considered the date-palm as the most highly developed, since “it only lacks one thing further to reach (the stage of) an animal: to tear itself loose from the soil and to move away in quest for nourishment.”

The lowest animals “are adjacent to the region of plants: such are those animals which propagate like grass, being incapable of mating […], e.g. earthworms, and certain insects”.The animals “which reach the stage of perfection […] are distinguished by fully developed weapons”, such as antlers, horns, teeth and claws. Tusi described these organs as adaptations to each species’s lifestyle, in a way anticipating natural theology. He continued:

“The noblest of the species is that one whose sagacity and perception is such that it accepts discipline and instruction: thus there accrues to it the perfection not originally created in it. Such are the schooled horse and the trained falcon. The greater this faculty grows in it, the more surpassing its rank, until a point is reached where the (mere) observation of action suffices as instruction: thus, when they see a thing, they perform the like of it by mimicry, without training […]. This is the utmost of the animal degrees, and the first of the degrees of Man in contiguous therewith.” Thus, in this paragraph, Tusi described different types of learning, recognising observational learning as the most advanced form, and correctly attributing it to certain animals.

Tusi seems to have perceived man as belonging to the animals, since he stated that “the Animal Soul [comprising the faculties of perception and movement …] is restricted to individuals of the animal species”, and that, by possessing a “Human Soul, […] mankind is distinguished and particularized among other animals.”

Some scholars have interpreted Tusi’s biological writings as suggesting that he adhered to some kind of evolutionary theory. However, Tusi did not state explicitly that he believed species to change over time.

Logic

In logic al-Tusi followed the teachings of ibn Sina. He wrote five works on the subject, the most important of which is one on inference. In Street describes this as follows:-

Tusi, a thirteenth century logician writing in Arabic, uses two logical connectives to build up molecular propositions: ‘if-then’, and ‘either-or’. By referring to a dichotomous tree, Tusi shows how to choose the proper disjunction relative to the terms in the disjuncts. He also discusses the disjunctive propositions which follow from a conditional proposition

Chemistry

Tusi contributed to the field of chemistry, stating an early law of conservation of mass

References

- Ṭūsī, Naṣīr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad; Badakchani, S. J. (2005), Paradise of Submission: A Medieval Treatise on Ismaili Thought, Ismaili Texts and Translations, 5, London: I.B. Tauris in association with Institute of Ismaili Studies, pp. 2–3, ISBN 1-86064-436-8

- Bennison, Amira K. (2009). The great caliphs : the golden age of the ‘Abbasid Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-300-15227-2.

- http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Tusi_Nasir.html

- Goldschmidt, Arthur; Boum, Aomar (2015). A Concise History of the Middle East. Avalon Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8133-4963-3.

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/the-cambridge-history-of-science/islamic-mathematics/4BF4D143150C0013552902EE270AF9C2

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasir_al-Din_al-Tusi

- https://www.al-islam.org/al-tawhid/vol8-n2/alleged-role-khawajah-nasir-al-din-al-tusi-fall-baghdad

DUA: Allah please accept this from us. You are All-Hearing and All-Knowing. You are The Most Forgiving.You are The Most Relenting and repeatedly Merciful. Allah grant us The Taufiq to read all the 5 prayers with sincerity.

(Taken from: To Be Earnest In Prayers By Amina Elahi)

■ Feel Free to Share the posts with your Friends…

■ You too can take part and help us in sharing the knowledge…

■ May ALLAH SWT reward you for conveying His Message To Mankind

Great